Researchers Identify New Genes Linked to Risk of COPD, Pulmonary Fibrosis

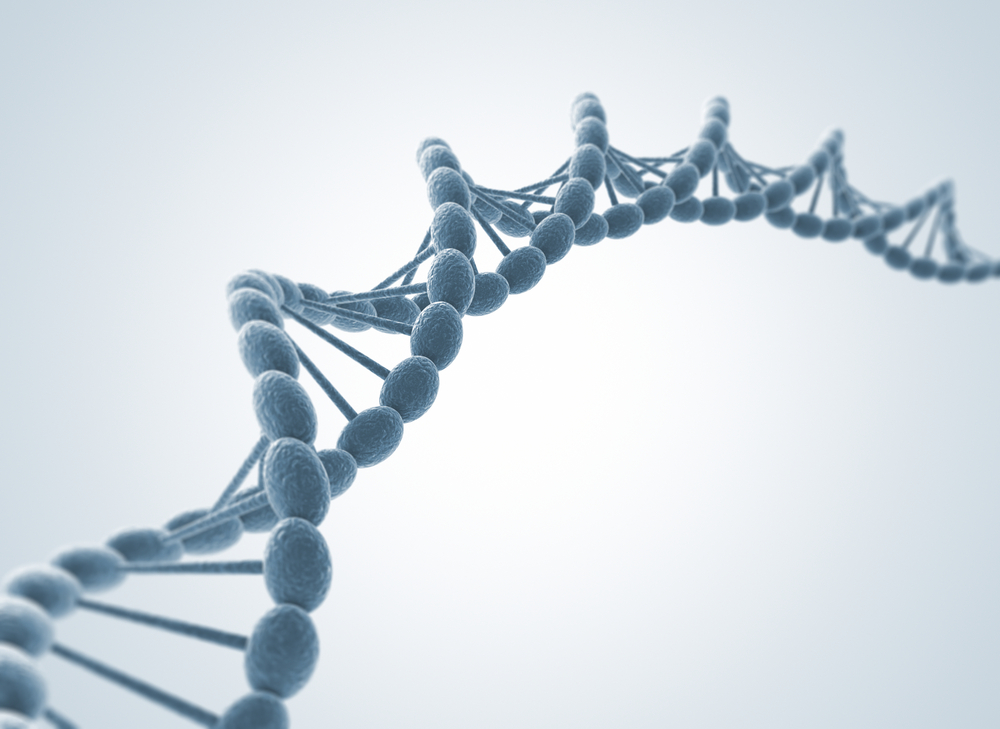

Researchers have identified new genes that play a role in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other lung-associated diseases, such as asthma and pulmonary fibrosis.

In a large consortium study led by Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), researchers described 13 new genetic markers that have not been associated with COPD before; four of these had not yet been linked to any lung function or trait, even in control cases.

“We are excited about these findings because we have not only uncovered new genetic risk factors for COPD, but also shown overlap of COPD genetic risk with the risk to asthma and pulmonary fibrosis,” said Brian Hobbs, MD, MMSc, lead scientist of the study, in a news release.

In the study, “Genetic loci associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap with loci for lung function and pulmonary fibrosis,” published in the journal Nature Genetics, researchers conducted a genetic association study with 15,256 cases and 47,936 controls. The results were replicated in a smaller cohort group (9,498 cases and 9,748 controls).

The team identified 22 genetic regions associated with COPD, of which 13 represented new associations with the disease. Nine of the newly discovered genetic regions were known to play roles in lung function in the general population, but not in COPD.

Two of the regions were previously reported to have an association with pulmonary fibrosis; however, genetic variants in these regions increased the risk for COPD and decreased the risk for pulmonary fibrosis.

“Now that we know there are new regions of the genome associated with COPD, we can build on this research by probing new biological pathways with the ultimate goal of improving therapies for our patients with this [and other] disease,” Hobbs said.

The study also took into account the effects of age, gender, and cigarette smoking on disease risk. Smoking was still identified as the single most important risk factor, yet the team now knows there is a genetic component as well.

“While it is extremely important that patients not smoke for many health reasons — including the prevention of COPD — we know that smoking cessation may not be enough to stave off the disease,” said Michael Cho, MD, MPH, a senior team member and physician-researcher in the BWH Channing Division of Network Medicine and Pulmonary and Critical Care Division.

“Many patients with COPD experience self-blame, but they may be comforted to know that genetics does play a role in who ultimately develops the disease,” he added.

The study is part of a larger research project begun in 2010 by the International COPD Genetics Consortium, a collaborative research effort at a BWH conference. The consortium now involves more than 20 studies in various countries.

COPD is currently the third-leading cause of disease in the U.S., and a condition prevalent worldwide. The findings of this study increase the understanding of underlying genetic risks of COPD or diseases that initially present as COPD.

“This work is representative of the importance of global collaboration and the shared goal of improving care for patients everywhere,” Cho said. “We’re grateful for the efforts of all of the authors, each of whom played a valuable role in this discovery.”