Astegolimab Lifts Quality of Life For Those With Frequent Flare-ups

Written by |

Patients with moderate-to-very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and frequent flare-ups who were given astegolimab, a medicine in Genentech’s pipeline, reported a better health-related quality of life than those taking a placebo, a study found.

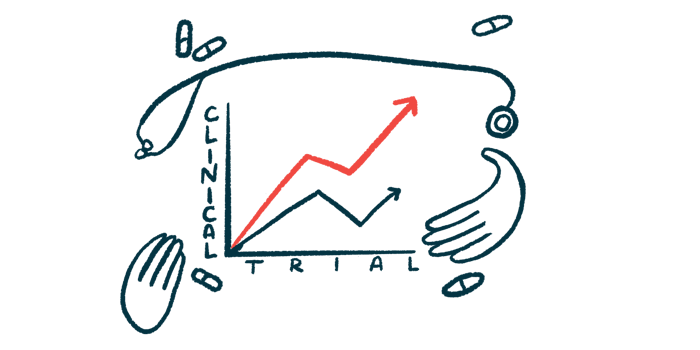

The findings are from a Phase 2a trial, called COPD-ST2OP (NCT03615040), that investigated how safe astegolimab is and how well it works to reduce episodes of symptom worsening, called flare-ups, in patients with moderate-to-very severe COPD.

Those given astegolimab also saw a reduction in flare-up frequency, although it was not significant compared to those on a placebo.

“We have not had any new treatments for COPD for several years now. This early trial of [asteogolimab] suggests we can reduce the number of lung attacks they have and improve patients with COPD quality of life,” Neil Greening, PhD, one of the study’s authors, said in a press release. Greening is an associate professor at the University of Leicester.

“The next few years are going to be an exciting time for COPD research and treatment,” Greening said.

The study, “Astegolimab, an anti-ST2, in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD-ST2OP): a Phase 2a, placebo-controlled trial,” was published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

Astegolimab is a fully human antibody designed to inhibit interleukin-33 (IL-33) from binding to the ST2 receptor, a protein that sits on the outer side of some cells.

“The epithelial-derived IL-33 and its receptor ST2 have been implicated in airway inflammation and infection,” the researchers wrote. Therefore, preventing them from binding to one another could ease COPD symptoms by reducing airway inflammation and infection that are present in patients with the disease.

COPD-ST2OP included 81 patients, ages 40 years or older, who had a diagnosis of moderate-to-very severe COPD and at least two flare-ups in the previous year. They were either current smokers or former smokers who had smoked for at least 10 years.

Of the 81 patients, 42 were given a subcutaneous (under-the-skin) injection of 490 mg of astegolimab every month for almost a year (44 weeks). The remaining 33 were given a placebo. Injections were performed using an infusion pump. All were asked to continue with their current medications for the duration of the trial.

The study’s primary endpoint was to evaluate the frequency of moderate-to-severe flare-ups until week 48. Secondary goals included assessing how frequently side effects occurred until week 60 to assess safety, patients’ health-related quality of life using Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire for COPD (SGRQ-C), and lung function based on forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). FEV1 is a lung function parameter that measures the amount of air a patient is able to exhale in one second.

Researchers also looked at the number of inflammatory cells in blood and sputum, the mucus brought up from the lungs by coughing.

When researchers looked at the frequency of flare-ups, they found it was 22% lower in the astegolimab group than in the placebo group (2.18 vs. 2.81). While this does not represent a statistically significant reduction, it’s greater than that seen previously with treatments targeting inflammatory pathways in COPD patients.

The researchers also looked at data from the SGRQ-C. They found the mean difference between the astegolimab group and the placebo group was –3.3, indicating an increase in health-related quality of life among those given astegolimab.

For FEV1, the mean difference between the two groups was 40 mL, reflecting an improvement in lung function in the astegolimab group.

The researchers also found these benefits were greater in patients with certain genetic and blood inflammation markers.

“In patients with moderate-to-very severe COPD and a history of frequent exacerbations, we found that compared with placebo, patients who received astegolimab for 48 weeks had a reduction in the frequency of attacks and improvement in the way they feel. Improvements were related to measurements in the participants’ blood and their genetic make-up,” Chris Brightling, MD, a professor of respiratory medicine at the University of Leicester and the trial’s chief investigator, said.

The frequency of side effects was similar between the two groups.

“These early results are really exciting and represent a potential new treatment for COPD. It will be important to run more trials of anti-ST2 therapeutics in larger patient groups, and to divide patient groups by the type and severity of their COPD symptoms to tailor medicines to different groups,” Ahmed Yousuf, a clinical academic fellow at the University of Leicester and the study’s first author, said.

The trial was sponsored by Genentech and coordinated by the National Institute for Health Research Leicester Biomedical Research Centre, where it took place.