Worse COPD outcomes linked with S. maltophilia bacterium in lungs

Higher mortality, greater hospitalization risk due to disease exacerbations

The bacterium Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in the lungs is significantly associated with a higher risk of death and hospitalization due to disease exacerbation in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a study shows.

Researchers are calling for clinical trials to test whether targeting S. maltophilia with antibiotics might improve outcomes for COPD patients who have these bacteria in their lungs.

The study, “Mortality and exacerbations associated with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A regional cohort study of 22,689 outpatients,” was published in Respiratory Research.

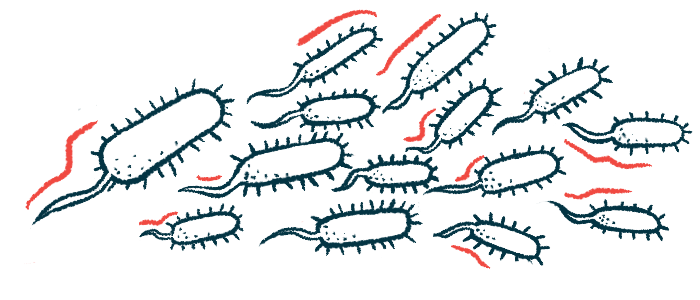

First discovered in the 1940s, S. maltophiliais is an opportunistic bacterium found in several environments, including soil, water, food, and plants. It’s responsible for infections and deaths in hospitalized patients, particularly those with a compromised immune system, due to its resistance to several antibiotics.

Research has suggested S. maltophilia in the lungs of COPD patients may drive exacerbations, or periods when COPD symptoms suddenly worsen, and might be associated with a twofold increase in mortality.

Outcomes with S. maltophilia infection

These studies were case reports or included a small number of patients, however, leading researchers in Denmark to assess whether having S. maltophilia in the lungs was associated with a higher risk of death and exacerbation-related hospitalization in a large group of COPD patients.

Using data from national registries and databases, they identified 22,689 COPD patients in an outpatient clinic visit in Eastern Denmark from 2010 to 2017. A total of 459 patients (2%) were positive for S. maltophilia in their lungs on a given test and 79% of those with follow-up testing remained positive for the bacterium.

Still, there were no “follow-up lower respiratory tract samples from approximately half the patients positive for S. maltophilia,” the researchers wrote.

Compared with the patients who tested negative for the bacterium, those with S. maltophilia had significantly poorer lung function, more severe shortness of breath, and lower body mass index (BMI, a ratio of height and weight). They were also significantly more likely to have severe exacerbations and to be a former smoker.

During the study, more than half (52.9%) the patients who were positive for S. maltophilia died, compared with only about one in three (34.4%) who were negative.

Also, the 459 S. maltophilia-positive patients were hospitalized a total of 1,100 times due to COPD exacerbations, while 22,230 patients without it had 23,821 hospitalizations.

Statistical models accounting for potential influencing factors, including age, sex, BMI, lung function, severe exacerbations, smoking status, and treatment patterns, showed that testing positive for S. maltophilia was significantly and independently associated with a more than a twofold higher risk of death. The risk of hospitalization for COPD exacerbation also was more than twice as high for S. maltophilia-positive patients relative to those without the bacterium in their lungs.

“We show, in an unselected, well-characterized, Danish population of COPD outpatients, that a lower respiratory tract sample positive for S. maltophilia is associated with a substantial increase in mortality and hospitalization for exacerbation of COPD,” wrote the researchers, who noted the “results were robust to multiple sensitivity analyses and seem biologically plausible.”

“Clinicians should be aware of this [microbe] as a possible cause, or at least marker, of clinical decline and events” in COPD, they said, recommending appropriately controlled trials wherein patients with “such a positive culture are allocated to a relevant antibiotic therapy or placebo.”